The Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, known locally as the Duomo.

Something bothers me when viewing the magnificent churches of Europe.

I have great respect for the artistic and scientific talents of the architects and builders. I admire the painstaking work of the masters who created the paintings, statues, columns, sarcophaguses, murals, mosaics, cornices, tapestries and frescoes that seem to decorate every available space. The reverence of these ancient people is touching and I respect the expressions of faith that these churches and their art represent.

But it also feels at times too much.

As my companion and I walked away from the glorious Duomo in Siena, Italy, we passed a group of English-speaking teen-agers getting their first glimpse as they rounded the corner. “How many, like, insanely beautiful churches can there be in one country?” a youth asked rhetorically of his peers.

Indeed, beautiful and plentiful. But on some level insane.

As a visitor to Italy centuries after the Renaissance artists, I am thankful for their contribution to art and beauty. That they elevated humanity is, to me, beyond question.

My father enjoyed painting. While his favorite subjects were sunsets and other landscapes that celebrated the beauty of creation, a few had religious themes. Some of his works hang (or did at one time) in the churches where he served as pastor or perhaps in some he visited. I grew up appreciating the talent and inspiration of the artist.

I’m grateful for the Medicis and other wealthy people who fostered an appreciation of art here. While I’m proud of Dad’s artwork, I recognize the difference between a hobby artist and a master. To become a master, one must work full-time for years. That requires support of wealthy people or wealthy institutions such as churches, either to buy the work or to sponsor it.

Cathédrale Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Lyon, France

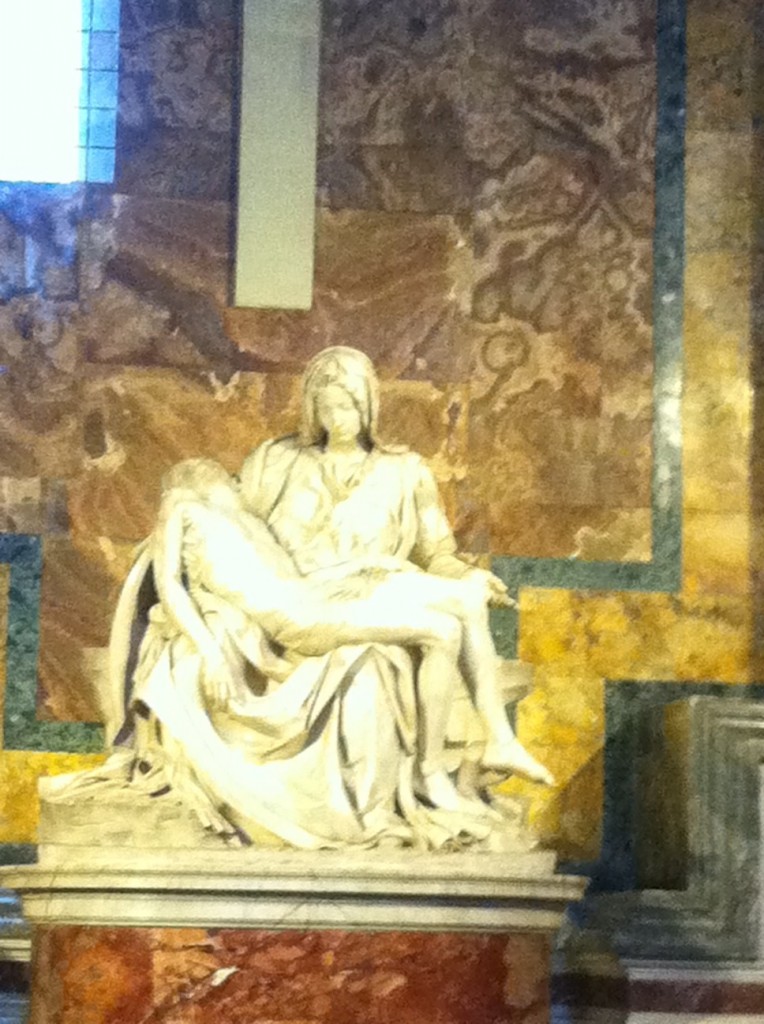

As I noted in an earlier post from this trip, I was in awe of the vision and execution that created the David. Sunday we saw the Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican and marveled again at the beauty and the talent that created it.

Michelangelo’s genius did not grow from nothing. He and Leonardo da Vinci were the greatest artists of a culture that also produced masters such as Botticelli and Donatello (both of whose works we’ve seen on this trip) and lesser masters whose names I’ve already forgotten but who produced magnificent works we viewed in the museums, cathedrals and basilicas we’ve toured. Their work grew from the generosity of the Medicis and other patrons of the arts and from a culture that honored and elevated art.

It’s the cavernous cathedrals that strike me as too much. While I know they were built as tributes to God, I wonder how much they really are statements about the money and might of man. Wouldn’t the savior so often depicted in these statues and paintings have preferred that the church spend more of its wealth following his commandments, such as feeding and clothing the poor, and less building such grand palaces of worship?

I don’t wonder that in a condemning way. I know I don’t contribute enough to helping those less fortunate. And I’m certain the inspiration provided by religious art and architecture helps change lives and drives – directly or not – many of the countless acts of generosity by the faithful.

But as I admire the artistic gifts of the masters, I wonder if the popes and bishops who built these grand cathedrals weren’t glorifying themselves at least as much as the master they served.